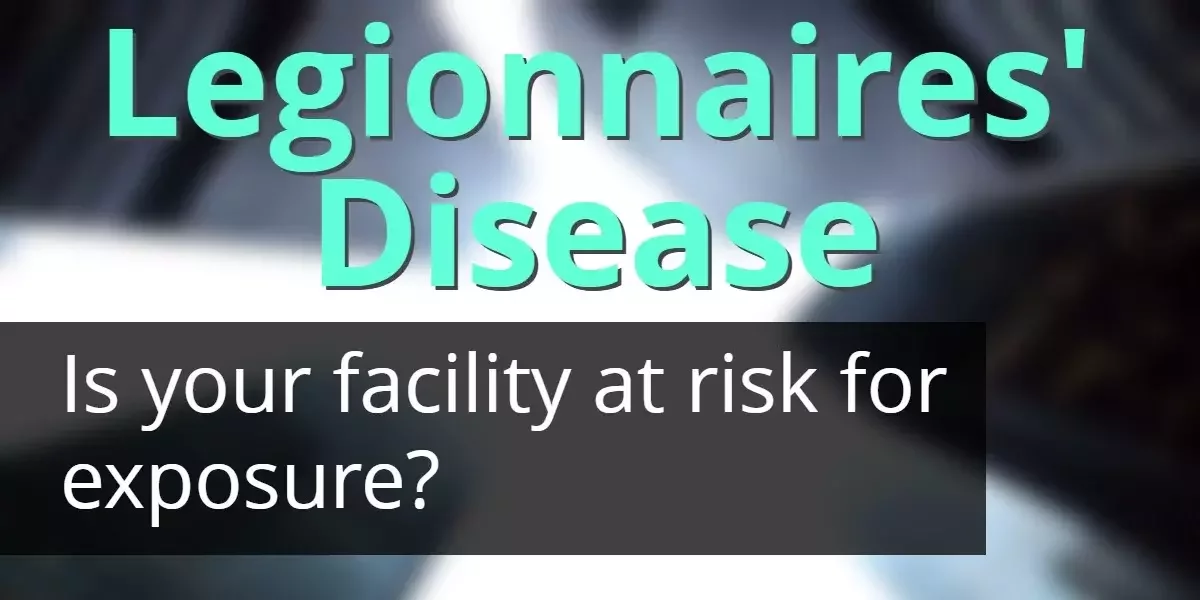

Legionnaires' Disease, is your facility at risk?

Sources

Aleccia, J. (2016, September 14). Ice machine, sinks linked to Legionnaires' cases at UW Medical Center. Retrieved from Seattle Times: http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/uw-medical-center-reports-2nd-death-from-legionnaires-bacteria-is-in-water-supply/

Centers for Disease Control. (2016, May 31). Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever). Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/legionella/fastfacts.html

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2016, September 24). Legionnaires' disease. Retrieved from Mayo Clinic: http://www.mayoclinic.org/home/ovc-20242041 (link no longer available)

McWhirter, C. (2016, June 7). CDC Warns of More Instances of Legionnaires’ Disease. Retrieved from The Wall Street Journal: http://www.wsj.com/articles/cdc-warns-of-more-instances-of-legionnaires-disease-1465318948

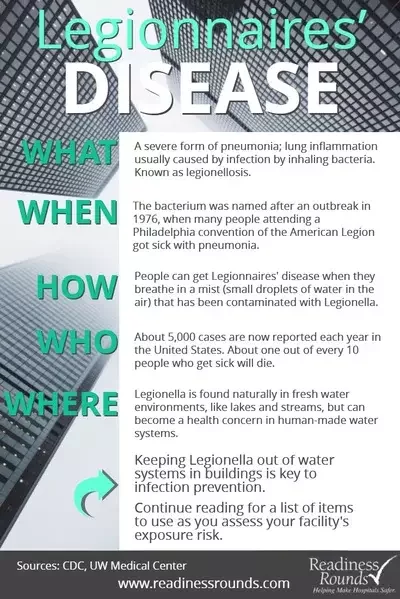

Szabo, L. (2016, June 7). Legionnaires' disease diagnoses quadrupled since 2000. Retrieved from USA Today: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/06/07/cdc-most-legionnaires-disease-outbreaks-preventable/85518646/

The Joint Commission. (2016). The Joint Commission E-dition. Retrieved from Accreditation Requirements, Environment of Care (EC): https://e-dition.jcrinc.com/MainContent.aspx (link no longer available)